Written by Michael LaPick

Healthcare Writer

We want to help you make educated healthcare decisions. While this post may have links to lead generation forms, this won’t influence our writing. We adhere to strict editorial standards to provide the most accurate and unbiased information.

Capitalism 101 teaches that prices rise where market competition is weak, and fall where competition is robust. Health insurance under the Affordable Care Act (aka Obamacare) offers a case in point.

From the ACA’s launch in 2011 to 2016, the price of the average benchmark premium (the second cheapest silver plan) remained under $300. Meanwhile, market concentration as measured by the market share of the largest insurer in each state held steady or dropped.

“They entered the first open enrollment period in 2013 without knowing how the composition of their individual member base would play out,” explains HealthCare.com co-founder Howard Yeh. “It was a land grab because every insurer was trying to build share in the individual market.”

The Marketplace Shakes Out

The election of Donald Trump as president in 2016 coincided with a rise in market concentration as insurers left marketplaces. Data gathered by the Urban Institute show that insurer participation in select regions sagged from 166 in 2017 to 149 in 2018.

“Insurance companies have only one chance each year to set the price,” notes Yeh. “If they price too low, they risk losing money for a full year until they can set a higher price. In the simplest terms, this is what happened.”

Beset by troubles, only 3 of 23 nonprofit health insurance co-ops born from the Affordable Care Act remained by 2020.

The drop in insurers and the corresponding rise in market concentration is associated with a big jump in premiums. The average benchmark premium leaped from $359 in 2017 to $481 in 2018.

States with More Insurers Tend to Have Lower Premiums

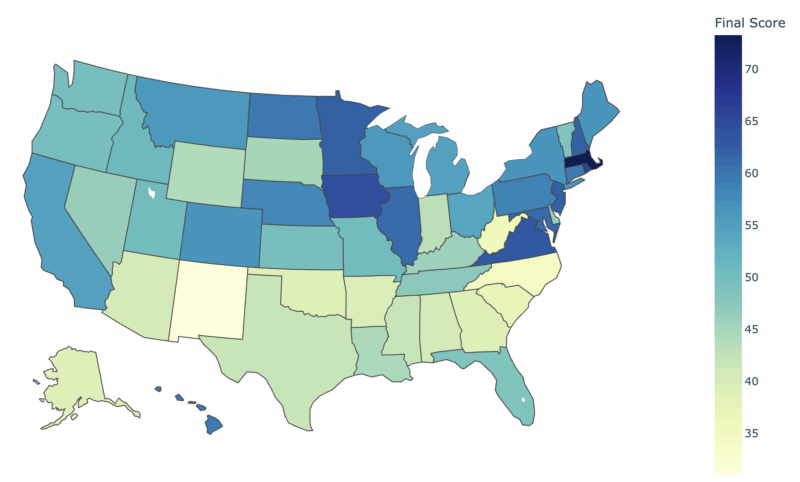

Looking across the 50 states, it becomes clear that states with less market concentration tend to have cheaper premiums. The below chart shows the relationship between the market share held by the largest insurer in each state and the state’s benchmark premium for 2019. The line indicates a moderate positive relationship between market concentration and premiums.

In the most expensive state Wyoming, the largest insurer holds 98% of the market. The average premium there is $858.

In the cheapest state Minnesota, the largest insurer holds just 37% of the market. The benchmark premium? $313.

The Urban Institute’s ACA expert John Holahan says their study found a particularly strong correlation between market concentration and premiums when there are two or fewer providers.

“Compared with, say, five insurers, you get an awful lot of competition and premiums tend to be low,” he told HealthCareInsider. “This happens particularly if one is a Medicaid provider, because everyone has to compete with Medicaid premiums, which tend to be cheap.”

The association between market concentration and premiums is clear, but the correlation can be even starker at the local level. A state may have ratings regions that are very concentrated within a state that as a whole is not concentrated. For instance, a state can have rural regions where a handful of carriers dominate while that is not the case elsewhere.

Cause for Optimism

After a period of rising market concentration and premiums from 2016 to 2018, the trend reversed and insurers began to come back to the marketplaces.

Insurer participation in the Urban Institute’s study regions rose from 149 in 2018 to 224 in 2021. In the same period, the average benchmark premium eased from $481 in 2018 to $452 in 2021.

“For a lot of insurers it’s risky coming into the marketplace because they may end up with no market share,” Holahan explains. “Clearly the market is now sending them the message that they can come in and do well,” he continues. “You’ve got the Oscars coming in, Blue Cross expanding, and United and Cigna starting to come back. If the reason they were staying out was risk, and they perceive that risk has gone down a lot, then it makes sense to come in.”

Insurer Participation in Select Study Regions, 2017–21

| Insurer | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

| Blue Cross Blue Shield | 35 | 34 | 34 | 36 | 40 |

| Anthem | 16 | 8 | 10 | 11 | 13 |

| UnitedHealthcare | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 11 |

| Cigna | 5 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 8 |

| Humana | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Aetna | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bright Health | 0 | 1 | 2 | 7 | 9 |

| Oscar | 3 | 6 | 10 | 17 | 21 |

| Centene | 21 | 23 | 28 | 29 | 34 |

| Molina | 12 | 12 | 12 | 13 | 13 |

| CareSource | 6 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 |

| Kaiser Permanente | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 |

| Other | 45 | 41 | 44 | 44 | 55 |

| Total number of participating insurers | 166 | 149 | 165 | 183 | 224 |

Note: This analysis excludes Anthem.

After years in which the Trump administration took steps such as ending the individual mandate to buy insurance, which experts say sent uncertainty into the ACA markets and prompted an exodus of insurers, the table has turned.

“The marketplaces have stabilized in terms of enrollment and even gone up,” Holahan notes. “And they’ll go up now with the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) premium subsidies and the possibility of them being extended. Insurers are seeing the market is stable and thinking they can make money if they come back.”

What Does It Mean for Me?

Competition and lower prices mean more choices and cheaper insurance premiums. But the calculus can become more complicated for consumers choosing among Obamacare plans.

“If I’m in a competitive market, I’m going to see a lot of products out there,” Holahan notes. “Some of the basic silver plans may be cheap due to small provider networks that I may worry about because I won’t be able to get the hospital I’d like to go to. So I may be willing to spend more to get a gold plan.”

Until recently, people with incomes above 400% of the federal poverty level have been stuck paying the full sticker price of ACA plans. But the Biden administration’s ARPA subsidies have – for now – capped premiums at no more than 8.5% of income for everyone. This motivates higher earners to purchase plans on the marketplaces.

Other factors keeping prices low include the Supreme Court’s recent ACA ruling confirming the landmark health reform law and the possibility of the ARPA subsidies being extended. These encourage insurers and customers to stick with the marketplaces, boosting competition – and the cheaper premiums that come with it.

On the downside, however, the Biden administration’s extension of open enrollment until August 15th in 2021 could eventually result in higher premiums as the pool of insured individuals becomes less healthy.

“This change has a good chance of resulting in higher pricing,” Yeh, HealthCare.com’s co-founder, says. “When insurers priced their coverage, they didn’t account for an extended special enrollment period. As a result, they may incur greater losses than they projected, which will, in turn, lead to higher premiums when they are next able to re-price their coverage.”

Thank you for your feedback!

“Individual Insurance Market Competition.” Kaiser Family Foundation. Accessed June 27, 2021.

“Obamacare Co-Ops Down From 23 to Final ‘3 Little Miracles’.” KHN. Accessed June 28, 2021.

Holahan, John, Banthin, Jessica and Erik Wengle. “Marketplace Premiums and Participation in 2021.” Urban Institute, p.13.

“Marketplace Premiums and Participation in 2021.” Urban Institute, p.13.